In this guide

- What tax do I pay on my super savings?

- What’s the proportioning rule?

- Tax free or taxable: What are the different components of your super benefit?

- Where does the proportioning rule come in?

- What impact can the proportioning rule have on super strategies?

- Common questions about the proportioning rule

- Get more guides like this with a free account

When it comes to your super, tax is always an important consideration – both when you make a contribution and when you finally get to take your money out of super on retirement.

As the super system offers special tax benefits designed to help you save for your retirement, there are strict rules in place covering when you qualify to withdraw your super savings and how much tax you need to pay on them.

The proportioning rule is one of these tax rules. It governs how the tax components of your superannuation withdrawals are calculated.

What tax do I pay on my super savings?

Before diving into the complexities of the proportioning rule, it’s worth briefly covering the basics about withdrawing your super and how much tax you pay at different ages.

In most cases, to withdraw from your super you need to have reached your preservation age (currently 60) and met a condition of release. Your super can only be accessed early in specific circumstances, such as becoming permanently disabled, being diagnosed with a terminal illness or if you face severe financial hardship.

If you’re eligible to withdraw your super, the tax rate you will pay on your savings depends on your age.

If you withdraw some of your super benefit before you reach age 60, you will generally pay tax on the taxable components of your super savings (there are exceptions if you have a terminal illness or the amount is a death benefit).

On the other hand, if you wait until you reach age 60, your withdrawal will be tax free unless it contains an untaxed element. Untaxed elements come from untaxed super funds, which are rare.

No tax is payable on the tax-free component of your super, regardless of your age when you make a withdrawal.

What’s the proportioning rule?

The main idea behind the proportioning rule is to prevent super fund members from trying to lower their tax bill if they decide to withdraw some or all of their super benefit.

Your super benefit consists of both tax-free and taxable components (see explanation below).

As there is no tax payable on the tax-free components of your super benefit, the proportioning rule is designed to stop you from cherry-picking between the tax-free and taxable parts of your super benefit and taking more of your benefit from the tax-free component as a way to reduce any tax payable on your super withdrawal.

Under the proportioning rule, the amount you withdraw from your account will be considered by the ATO to have been paid to you in the same proportions as the tax-free and taxable components making up your super benefit.

If you’re aged 60 or more and not a member of an untaxed fund, you may wonder why proportioning should matter to you considering both the taxable and tax-free components of your super will be paid to you free from tax. The answer is that if your super is paid to a person who is not a tax dependent (such as your adult child) after your death, they will pay tax on the taxable components of the benefit.

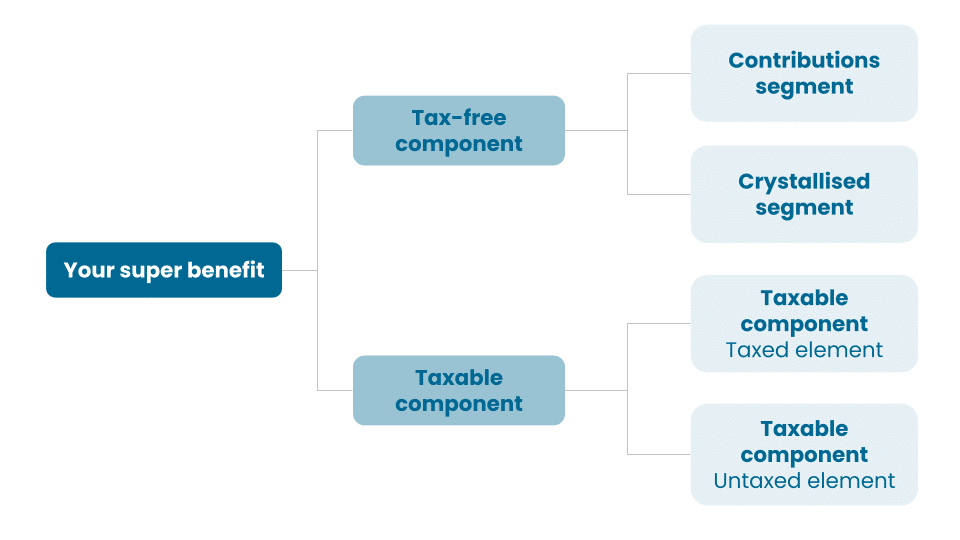

Tax free or taxable: What are the different components of your super benefit?

Your super account is broken up into tax-free and taxable components depending on how the original contributions were made into your super account:

1. Tax-free component

- This mainly consists of your non-concessional (after-tax) contributions, as these come from income on which you have already paid tax. (If you were a member of a super fund before July 2007, you may also have other tax-free amounts in your super account.)

Within your tax-free component there are two different elements:

- Contributions segment – This is generally all contributions made into your super account after 30 June 2007 that have not been included in the super fund’s assessable income. These are mostly contributions where you have not claimed a tax deduction, such as non-concessional (after-tax) contributions.

- Crystallised segment – This is any amounts that would have been tax free if they had been paid to you before 1 July 2007. Examples are undeducted contributions made before 30 June 2007, CGT-exempt components and pre-July 1983.

2. Taxable component

The taxable component is the remainder of your account balance (i.e. any amount that is not tax-free component). This comes from concessional (before-tax) contributions and investment earnings, so the value of this component changes regularly.

Within your taxable component there are two different elements:

- Taxable component – taxed element: In most cases your super fund will have paid the 15% contributions tax on the super contributions or investment earnings making up your taxable component.

- Taxable component – untaxed element: If your super fund has not paid tax on the contributions or earnings making up your taxable component, those amounts are called the untaxed element of your taxable component. (This only applies to members of untaxed super funds run by the Commonwealth or a state or territory government)

Your annual statement from your super fund will normally indicate both the tax-free and taxable components of your super account. If not, call your fund and they will work it out for you.

Where does the proportioning rule come in?

Once you know the tax-free and taxable component percentages of your super benefit, the proportioning rule requires any withdrawals you make to be in the same pre-determined percentages. For example, if the total value of your super benefit has a 40% tax-free component and a 60% taxable component, your benefit withdrawal must also comprise a 40% tax-free component and 60% taxable component.

You can’t choose the component from which you would like your benefit withdrawal to be paid, which means you can’t choose to withdraw just from your tax-free component.

The proportioning rule doesn’t apply to the payment of super benefits consisting entirely of a tax-free or a taxable component. These include:

- Government co-contribution payments only made up of a tax-free component

- Superannuation Guarantee (SG) payments only consisting of a taxable component

- Contribution-splitting payments only consisting of a taxable component.

What impact can the proportioning rule have on super strategies?

The proportioning rule is important when it comes to estate planning because beneficiaries who are not tax dependants will be liable for tax on taxable components of superannuation death benefits they receive.

A recontribution strategy can be employed to convert taxable components into a tax-free component by withdrawing money from super and using the funds to make non-concessional (after-tax) contributions. These contributions can potentially be quarantined in a separate account to be passed on to a beneficiary who is not a tax dependant while other super accounts containing taxable components can be left to dependant beneficiaries who will not pay tax. If you are drawing retirement income from super, this is called the dual pension strategy.

Common questions about the proportioning rule

The following questions were raised by members in our Q&A webinars.

Get more guides like this with a free account

better super and retirement decisions.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.